This post will probably only make sense to those deeply involved in Mastodon and the fediverse. So if that’s not your thing, or you’re not interested in issues of social media and safety online, you may want to skip this post.

I keep thinking of the Wil Wheaton fiasco as a kind of security incident that the Mastodon community needs to analyze and understand to prevent it from happening again.

Similar to this thread by CJ Silverio, I’m not thinking about this in terms of whether Wil Wheaton or his detractors were right or wrong. Rather, I’m thinking about how this incident demonstrates that a large-scale harassment attack by motivated actors is not only possible in the fediverse, but is arguably easier than in a centralized system like Twitter or Facebook, where automated tools can help moderators to catch dogpiling as it happens.

As someone who both administrates and moderates Mastodon instances, and who believes in Mastodon’s mission to make social media a more pleasant and human-centric place, this post is my attempt to define the attack vector and propose strategies to prevent it in the future.

Harassment as an attack vector

First off, it’s worth pointing out that there is probably a higher moderator-to-user ratio in the fediverse than on centralized social media like Facebook or Twitter.

According to a Motherboard report, Facebook has about 7,500 moderators for 2 billion users. This works out to roughly 1 moderator per 260,000 users.

Compared to that, a small Mastodon instance like toot.cafe has about 450 active users and one moderator, which is better than Facebook’s ratio by a factor of 500. Similarly, a large instance like mastodon.cloud (where Wil Wheaton had his account) apparently has one moderator and about 5,000 active users, which is still better than Facebook by a factor of 50. But it wasn’t enough to protect Wil Wheaton from mobbing.

The attack vector looks like this: a group of motivated harassers chooses a target somewhere in the fediverse. Every time that person posts, they immediately respond, maybe with something clever like “fuck you” or “log off.” So from the target’s point of view, every time they post something, even something innocuous like a painting or a photo of their dog, they immediately get a dozen comments saying “fuck you” or “go away” or “you’re not welcome here” or whatever. This makes it essentially impossible for them to use the social media platform.

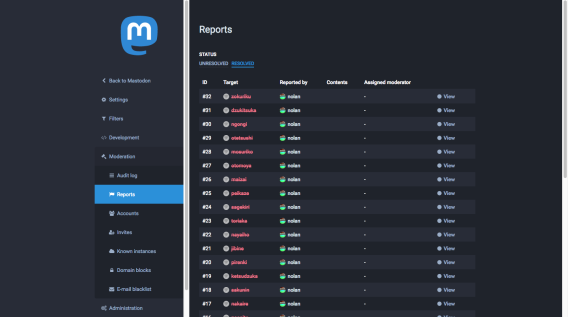

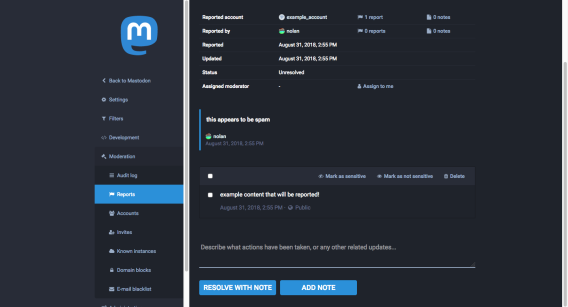

The second part of the attack is that, when the target posts something, harassers from across the fediverse click the “report” button and send a report to their local moderators as well as the moderator of the target’s instance. This overwhelms both the local moderators and (especially) the remote moderator. In mastodon.cloud’s case, it appears the moderator got 60 reports overnight, which was so much trouble that they decided to evict Wil Wheaton from the instance rather than deal with the deluge.

For anyone who has actually done Mastodon moderation, this is totally understandable. The interface is good, but for something like 60 reports, even if your goal is to dismiss them on sight, it’s a lot of tedious pointing-and-clicking. There are currently no batch-operation tools in the moderator UI, and the API is incomplete, so it’s not yet possible to write third-party tools on top of it.

Comparisons to spam

These moderation difficulties also apply to spam, which, as Sarah Jeong points out, is a close cousin to harassment if not the same thing.

During a recent spambot episode in the fediverse, I personally spent hours reporting hundreds of accounts and then suspending them. Many admins like myself closed registrations as a temporary measure to prevent new spambot accounts, until email domain blocking was added to Mastodon and we were able to block the spambots in one fell swoop. (The spambots used various domains in their email addresses, but they all used same email MX domain.)

This was a good solution, but obviously it’s not ideal. If another spambot wave arrives, admins will have to coordinate yet again to block the email domain, and there’s no guarantee that the next attacker will be unsophisticated enough to use the same email domain for each account.

The moderator’s view

Back to harassment campaigns: the point is that moderators are often in the disadvantageous position of being a small number of humans, with all the standard human frailties, trying to use a moderation UI that leaves a lot to be desired.

As a moderator, I might get an email notifying me of a new report while I’m on vacation, on my phone, using a 3G connection somewhere in the countryside, and I might try to resolve the report using a tiny screen with my fumbly human fingers. Or I might get the report when I’m asleep, so I can’t even resolve it for another 8 hours.

Even in the best of conditions, resolving a report is hard. There may be a lot of context behind the report. For instance, if the harassing comment is “lol you got bofa’d in the ligma” then suddenly there’s a lot of context that the moderator has to unpack. (And in case you’re wondering, Urban Dictionary is almost useless for this kind of stuff, because the whole point of the slang and in-jokes is to ensure that the uninitiated aren’t in on the joke, so the top-voted Urban Dictionary definitions usually contain a lot of garbage.)

So now, as a moderator, I might be looking through a thread history and trying to figure out whether something actually constitutes harassment or not, who the reported account is, who reported it, which instance they’re on, etc.

If I choose to suspend, I have to be careful because a remote suspension is not the same thing as a local suspension: a remote suspension merely hides the remote content, whereas a local suspension permanently deletes the account and all their toots. So account moderation can feel like a high-wire act, where if you click the wrong thing, you can completely ruin someone’s Mastodon experience with no recourse. (Note though that in Mastodon 2.5.0 a confirmation dialogue was added for local suspensions, which makes it less scary.)

As a moderator working on a volunteer basis, it can also be hard to muster the willpower to respond to a report in a timely manner. Whenever I see a new report for my instance, I groan and think to myself, “Oh great, what horrible thing do I have to look at now.” Hate speech, vulgar images, potentially illegal content – this is all stuff I’d rather not deal with, especially if I’m on my phone, away from my computer, trying to enjoy my free time. If I’m at work, I may even have to switch away from my work computer and use a separate device and Internet connection, since otherwise I could get flagged by my work’s IT admin for downloading illegal or pornographic content.

In short: moderation is a stressful and thankless job, and those who do it deserve our respect and admiration.

Now take all these factors into account, and imagine that a coordinated group of harassers have dumped 60 (or more!) reports into the moderator’s lap all at once. This is such a stressful and laborious task that it’s not surprising that the admin may decide to suspend the target’s account rather than deal with the coordinated attack. Even if the moderator does decide to deal with it, a sustained harassment campaign could mean that managing the onslaught has become their full-time job.

A harassment campaign is also something like a human DDoS attack: it can flare up and reach its peak in a matter of hours or minutes, depending on how exactly the mob gets whipped up. This means that a moderator who doesn’t handle it on-the-spot may miss the entire thing. So again: a moderator going to sleep, turning off notifications, or just living their life is a liability, at least from the point of view of the harassment target.

Potential solutions

Now let’s start talking about solutions. First off, let’s see what the best-in-class defense is, given how Mastodon currently works.

Someone who wants to avoid a harassment campaign has a few different options:

- Use a private (locked) account

- Run their own single-user instance

- Move to an instance that uses instance whitelisting rather than blacklisting

Let’s go through each of these in turn.

Using a private (locked) account

Using a locked account makes your toots “followers-only” by default and requires approval before someone can follow you or view those toots. This prevents a large-scale harassment attack, since nobody but your approved followers can interact with you. However, it’s sort of a nuclear option, and from the perspective of a celebrity like Wil Wheaton trying to reach his audience, it may not be considered feasible.

Account locking can also be turned on and off at anytime. Unlike Twitter, though, this doesn’t affect the visibility of past posts, so an attacker could still send harassing replies to any of your previous toots, even if your account is currently locked. This means that if you’re under siege from a sudden harassment campaign that flares up and dies down over the course of a few hours, keeping your account locked during that time is not an effective strategy.

Running your own single-user instance

A harassment target could move to an instance where they are the admin, the moderator, and the only user. This gives them wide latitude to apply instance blocks across the entire instance, but those same instance blocks are already available at an individual level, so it doesn’t change much. On the other hand, it allows them to deal with reports about themselves by simply ignoring them, so it does solve the “report deluge” problem.

However, it doesn’t solve the problem of getting an onslaught of harassing replies from different accounts across the fediverse. Each harassing account will still require a block or an instance block, which are tools that are already available even if you don’t own your own instance.

Running your own instance may also require a level of technical savvy and dedication to learning the ins and outs of Mastodon (or another fediverse technology like Pleroma), which the harassment target may consider too much effort with little payoff.

Moving to a whitelisting instance

By default, a Mastodon instance federates with all other instances unless the admin explicitly applies a “domain block.” Some Mastodon instances, though, such as awoo.space, have forked the Mastodon codebase to allow for whitelisting rather than blacklisting.

This means that awoo.space doesn’t federate with other instances by default. Instead, awoo.space admins have to explicitly choose the instances that they federate with. This can limit the attack surface, since awoo.space isn’t exposed to every non-blacklisted instance in the fediverse; instead, it’s exposed only to a subset of instances that have already been vetted and considered safe to federate with.

In the face of a sudden coordinated attack, though, even a cautious instance like awoo.space probably federates with enough instances that a group of motivated actors could set up new accounts on the whitelisted instances and attack the target, potentially overwhelming the target instance’s moderators as well as the moderators of the connected instances. So whitelisting reduces the surface area but doesn’t prevent the attack.

Now, the target could both run their own single-user instance and enable whitelisting. If they were very cautious about which instances to federate with, this could prevent the bulk of the attack, but would require a lot of time investment and have similar problems to a locked account in terms of limiting the reach to their audience.

Conclusion

I don’t have any good answers yet as to how to prevent another dogpiling incident like the one that targeted Wil Wheaton. But I do have some ideas.

First off, the Mastodon project needs better tools for moderation. The current moderation UI is good but a bit clunky, and the API needs to be opened up so that third-party tools can be written on top of it. For instance, a tool could automatically find the email domains for reported spambots and block them. Or, another tool could read the contents of a reported toot, check for certain blacklisted curse words, and immediately delete the toot or silence/suspend the account.

Second off, Mastodon admins need to take the problem of moderation more seriously. Maybe having a team of moderators living in multiple time zones should just be considered the “cost of doing business” when running an instance. Like security features, it’s not a cost that pays visible dividends every single day, but in the event of a sudden coordinated attack it could make the difference between a good experience and a horrible experience.

Perhaps more instances should consider having paid moderators. mastodon.social already pays its moderation team via the main Mastodon Patreon page. Another possible model is for an independent moderator to be employed by multiple instances and get paid through their own Patreon page.

However, I think the Mastodon community also needs to acknowledge the weaknesses of the federated system in handling spam and harassment compared to a centralized system. As Sarah Jamie Lewis says in “On Emergent Centralization”:

Email is a perfect example of an ostensibly decentralized, distributed system that, in defending itself from abuse and spam, became a highly centralized system revolving around a few major oligarchical organizations. The majority of email sent […] today is likely to find itself being processed by the servers of one of these organizations.

Mastodon could eventually move in a similar direction, if the problems aren’t anticipated and headed off at the pass. The fediverse is still relatively peaceful, but right now that’s mostly a function of its size. The fediverse is just not as interesting of a target for attackers, because there aren’t that many people using it.

However, if the fediverse gets much bigger, it could became inundated by dedicated harassment, disinformation, or spambot campaigns (as Twitter and Facebook already are), and it could shift towards centralization as a defense mechanism. For instance, a centralized service might be set up to check toots for illegal content, or to verify accounts, or something similar.

To prevent this, Mastodon needs to recognize its inherent structural weaknesses and find solutions to mitigate them. If it doesn’t, then enough people might be harassed or spammed off of the platform that Mastodon will lose its credibility as a kinder, gentler social network. At that point, it would be abandoned by its responsible users, leaving only the spammers and harassers behind.

Thanks to Eugen Rochko for feedback on a draft of this blog post.

Posted by marcozehe on August 31, 2018 at 7:47 PM

Thank you for this post, Nolan! One thing I might add is a language barrier problem. If English is not a moderator‘s first language, it becomes even harder if the current crisis is English-based and a lot of slang is used that we don‘t learn at school. Even within the English-speaking world, local slang from Britain often enough baffles Americans, or any other combination. You mentioned the Urban Dictionary problem yourself. Now try to imagine the added struggle if the language a moderator has to deal with is not their native tongue…

Posted by Nolan Lawson on August 31, 2018 at 8:32 PM

This is another great point. I can’t imagine moderating something that isn’t in a language I understand. To be fair, though, Facebook and Twitter have similar problems, since even 7,500 people can’t know every language in the world. :)

Posted by Bookmarks for August 31st from 14:07 to 21:53 : Extenuating Circumstances on August 31, 2018 at 10:00 PM

[…] Mastodon and the challenges of abuse in a federated system | Read the Tea Leaves – […]

Posted by gehrehmee on August 31, 2018 at 10:48 PM

Something I’ve been thinking about in social media generally lately is the “squeaky wheel gets the grease” factor. Given a large enough population of users (and a successful federated space should have a big population), a very small fringe group can make a significant amount of “this should be stopped” signal, compared to the largely silent “everything’s fine” signal.

Do we need to consider some kind of “this is fine” moderation signal, even in some limited randomly sampled approach, to provide balance?

Do people flagging issues need to have some kind of reputation system to indicate their complaints are worth investigating? Slashdot moderation/meta-moderation comes to mind….

What else can be done to de-emphasize spurious complaint-abuse is a global-scale distributed federated network?

Posted by How to deal with “discourse” | Read the Tea Leaves on September 1, 2018 at 10:55 AM

[…] « Mastodon and the challenges of abuse in a federated system […]

Posted by The_Lex (@screwjaw) on September 1, 2018 at 11:19 AM

I’m just a user who experienced the Wheaton incident from the periphery that started following the matter because I follow a very vocal moderator committed to strong values. From this users experience, though, it got dealt with pretty swiftly compared to say a Facebook or Twitter who would have fought tooth and nail to NOT address the issue. Heck, just look at how long it took from Twitter to at least temporary ban Alex Jones! I know Mastodon is something of a reaction to that level of non-moderation, but I still want to say good work at the swift action.

I only got the gist of Wheaton’s pre-Mastodon problematics because of the Mastodon conflicts, but the discussions of how much work/knowledge a Mastodon moderator is expected to have from some in the community is astounding! I appreciate the Federation model, the self-direction of moderators/admins, and that some moderators/admins want to have strong moderation than Facebook and Twitter, but it’s amazing how even within that area, there’s a wide range of criteria among moderators/admins. . .and being open to the public pressure of users. This system feels a lot more democratic (or civic republican), but it definitely also has the noise issues that democracy has. . .just look at how much the noise level of US politics has gotten as it has gotten more democratic through the increased participation of super PACs and non-profits weakening the gate keeping of political parties (virtues and vices to both, but it has become MORE democratic even as we feel that the super PACs and non-profits are pushing for less justice/trust in the system).

I do wonder about the virtues and vices of the increased democracy/noise in the Fediverse by moderators/admins voicing their opinions/arguments to the public. Understandable that the Federation-model cuts down on the control of what becomes public or under wraps with the moderators/admins and the public, but it definitely piques my interest. It definitely makes for an interesting case study to me who has an anthropological, sociological, and political sciency/philosophical way of thinking about these things.

Posted by codesections on September 1, 2018 at 3:12 PM

Thanks for posting this; it gave me a lot to think about.

I posted my own thoughts—which build on these—at https://www.codesections.com/blog/mastodon-mobs-and-mastodon-mobs/

Posted by Joseph Hertzlinger on September 1, 2018 at 7:24 PM

A suggestion:

A new user is not permitted to post to an instance for 24 hours. A user is not permitted to respond to or report someone until they’ve followed that person for 24 hours.

If nothing else, that should slow down dogpiling.

OTOH, this post is a violation of that rule…

Posted by Nolan Lawson on September 2, 2018 at 11:28 AM

There is a suggestion of instance “greylisting” which is similar to this idea: https://github.com/tootsuite/mastodon/issues/4296

Posted by Sarah on December 24, 2018 at 9:04 PM

Better yet, make it so that you can only report that user if you belong to that instance. And then place a hard limit on the amount of people that can join that instance.

For me, I’m considering forking Mastodon, doing a complete reskin, and make it so that you can only report people if you belong to that specific instance.

To me this is the issue. And you have people like this one computer guy on Peertube, that absolutely love people’s ability to report across instances.

Which is so incredibly irresponcible to encourage that kind of behaviour.

Can you imagine if someone on Twitter could report someone for behaviour they did on Facebook? No, it just doesn’t happen or work that way.

Posted by guest on September 2, 2018 at 8:26 AM

Sorry, but moderation will not solve this problem, because it’s not a moderation problem. This is a problem with a society.

First of all, all who run from Twitter to Mastodon for having a community experience – it’s totally missing a point. That’s not about experience, that’s about connection with members. It doesn’t matter that you haven’t been on a beer with all of them, you knew them from their posts, from discussions, that was this connection I’m speaking about. This will not work with thousands of “friends” which are only for mutually pressing a “like” button. By going into community, reading their posts and writing own, user knows other members more and more and other members know user more and more. That’s how it was working in Internet forums in Web 2.0 era, that’s how it was going with personal webpages Web 1.0 era.

The problem is that it just cannot be done in modern, division-infested society. I type “division-infested” as most of these divisions are artificially induced not to make people to act efficiently and to govern them efficiently. And of course sell stuff, fueling the “holy wars” more and going from discussion to fallacies. More and more orthodox fighting camps are created, all brainwashed that all other sides are totally evil, and that’s how modern internet works. This is a totally opposite of community, which can be even created of people with conflicting opinions discussing them.

The problem is that we in generally spoken “Western” society are no better than religion fundamentalists from countries most of us consider “wild”, only the content is different. So Sorry, even if you place one moderator in the bottom of every user, this would not work… or would change into echo chamber.

Posted by Whatever on September 2, 2018 at 2:12 PM

“Someone who wants to avoid a harassment campaign has a few different options”

So it’s up to the person being harassed to fend on their own and be safe. Sorry but that’s not a “solution”. All I got from this is that the Mastodon model allows and encourages harassment of users, volunteer moderators and other admins, and abuse of the system. Ergo the model isn’t good and should be changed. Putting responsibility on possible victims isn’t a solution at all and shouldn’t even be suggested.

Posted by fazalmajid on September 2, 2018 at 3:22 PM

The admins who banned Wheaton are short sighted. The trolls making false abuse reports are the ones who should be banned. Someone else will be the target of their bile next week, and the admins will have 60 more spurious abuse reports to deal with. Perhaps then they will learn, and the platform develop tools for ((report abuse) abuse). Many legal traditions impose for calumny the same punishment as for the alleged offense itself, e.g. Icelandic or Islamic law.

As for the general viciousness, this shows it has nothing to do with the technology or centralization, but everything to do with open social networks with no non-verbal nuance. I’m not sure even a highly compartmented closed network like Facebook or Google Plus would be immune to this phenomenon.

Posted by svrtknst on September 3, 2018 at 1:02 AM

For the moderators, would a report cap or throttle be viable? E.g. if a certain account receives N reports over T time, where T is either a throttle, like “24 hours” or a cap like “until a moderator has reviewed the situation”, then new reports will be declined.

Say that an instance has a cap of 10 reports that will stay in effect until a mod reviews those reports. Someone on that instance has received 10 reports already, so when I report the user as well, I am possibly greeted with something like “The report cap for this user has been met. Your report has been noted”.

For the moderator, when they log on to the dashboard, they will see something like “Malicious User has 10 pending reports, with 54 reports in total”. If there are different categories, you could possibly work with groupings too (“there are 4 reports for harassment, 11 for hate speech, etc).

This could possibly make it a little less overwhelming for the moderator, without affecting the user space – It doesn’t make much if a difference if someone receives 5 or 50 reports. Mods will likely not deal with it sooner, a malicious actor will probably not cease their immediate behaviour when reported, and if there are automated responses like soft bans, they can be fired off at 10 reports just as well as 30 or 50.

Posted by svrtknst on September 3, 2018 at 1:03 AM

As for fasle accusations, there could probably be alleviations for that, too. Restrictions on newly created accounts (can’t post/report until a certain age), or on bad actors. N number of false reports and you lose that privilege, etc.

Posted by Lew Perin on September 19, 2018 at 7:33 AM

Thanks for this thoughtful post!

I just want to clarify one thing you said:

“And in case you’re wondering, Urban Dictionary is almost useless for this kind of stuff, because the whole point of the slang and in-jokes is to ensure that the uninitiated aren’t in on the joke, so the top-voted Urban Dictionary definitions usually contain a lot of garbage.”

Did you mean to say that trolls have intentionally polluted Urban Dictionary to make it harder for moderators?

Posted by It may be time to rethink our approach to moderation – Software and Other Shenanigans on September 21, 2018 at 10:04 PM

[…] the instance’s admin had to remove him as the only way to stop the flood. There’s an interesting blog post by Nolan Lawson about looking at this as an attack or harassment vector that got me thinking about some changes to […]

Posted by Bye bye Twitter, hello Masto ! – Framablog on September 27, 2018 at 10:46 PM

[…] sûr, Mastodon est loin d’être parfait – cette critique constructive de Nolan Lawson aborde certaines des plus grandes questions et plusieurs approches possibles – mais Mastodon […]

Posted by Tras unos meses en Mastodon – Angeles' blog on October 24, 2018 at 11:47 AM

[…] indias al ser la primera celebridad que llegó y abrumó a las instancias pequeñas, denotando que hacen falta mejores herramientas de gestión de informes de comportamiento inadecuado para los admin…, pero tampoco podemos negar que si el susodicho hubiese elegido una instancia mayor con mas […]

Posted by Sarah on December 24, 2018 at 8:42 PM

This is why I generally do not recommend Mastodon on my personal website. When there are places that don’t target individuals users for dogpiling, why is worth it to use a Social Network that can’t seem to get a real grip and realize they may have a real problem on their hands?

GNU Social and Pleroma already are slowly switching to a non TOS moidel, and not (obviously) showing where report buttons are.

That’s become Pleroma doesn’t need them, and they cause to much of a centralization problem on places like Mastodon.

Consider also that Pixiv runs their own Mastodon instance.

Posted by Christopher Price on February 1, 2019 at 1:38 AM

At least today, Mastodon.cloud appears to be hosted by a company in Japan. This raises the issue of having a node that is moderated by people speaking the same language.

I can’t see any popular Mastodon node purposefully evicting Will Wheaton over a few dozen abuse reports. Likely they evicted him because they didn’t know A) Who he was B) Why people were attacking him and C) What was being communicated.

Unfortunately for Will, the domain name is in English and there seems to be no disclaimer of this until you dig into the all-Japanese TOS. It was there that this all started to make sense to me.

Posted by Curbing Harassment with User Empowerment – Purism on August 8, 2019 at 7:25 AM

[…] truth is that a motivated mob can target anyone, marginalized or not. We would all benefit from effective anti-harassment […]

Posted by Mastodon and the challenges of abuse in a federated system | Read the Tea Leaves | Here, Read This on November 6, 2022 at 9:25 AM

[…] https://nolanlawson.com/2018/08/31/mastodon-and-the-challenges-of-abuse-in-a-federated-system/ […]

Posted by Mastodon moderation | Here, Read This on November 6, 2022 at 12:22 PM

[…] https://nolanlawson.com/2018/08/31/mastodon-and-the-challenges-of-abuse-in-a-federated-system/ […]

Posted by Scaling up virtual presence (and conversation) – RadOncNotes on November 14, 2022 at 5:15 PM

[…] you might read about Wil Wheaton’s failure to use Mastodon due to his popularity and another server operator’s take on the issue. You might be interested to learn that the oldest open Mastodon issue is six years old and asks […]

Posted by Scaling Mastodon is impossible - Mondaychick on November 15, 2022 at 1:16 AM

[…] instance you might read about Wil Wheaton’s failure to use Mastodon due to his popularity and another server operator’s take on the issue. You might be interested to learn that the oldest open Mastodon issue is six years old and asks for […]