Last week I was in a pub having drinks with some friends when we decided to play a little cribbage. Crib is a great card game – it’s fun and fast-paced, it works well with anywhere between 2 and 4 players, and you can finish a round in about a half-hour. It’s pretty much the perfect card game.

We didn’t have any pens or paper to keep score, though, so we turned to the Android Market to try to find a good scoring application. The first one we tried out, Score, crashed on us halfway through without saving our game. The second, Scorer, was workable but awkward. In the end, we were able to score our game, but it would have been much easier to just use pen and paper. Something about that struck me as wrong – this is the 21st century! Why can’t my damned smartphone keep score?

I like thinking about user interface problems, so I followed this rabbit hole all the way to the end. I tested the most popular scoring apps on the Android Market, found them all to be underwhelming, and then finally wrote my own. My app, KeepScore, only took one weekend to write, but I think it’s already better and more usable than every other scoring app on the Market.

What makes it better? My first advantage is simple hindsight. Since the other apps came out first, I was able to test them and see which design decisions worked and which ones didn’t. I remembered the frustrations that came with our impromptu game of cribbage: I pressed the wrong button! It didn’t save our scores! The screen fell asleep! Based on this experience, I knew what to avoid in KeepScore.

My second advantage is that I read and applied the principles in Joel Spolsky’s User Interface Design for Programmers. I mention this book a lot in my blog, but I just can’t emphasize enough how reading it can help make you a better UI designer. If there were two principles from this book that I wish every app developer would follow, it’s these:

- Assume your users are illiterate. They won’t read anything.

- Assume your users have big, fat thumbs. They can’t press anything accurately.

I won’t try to justify these principles here, because I think I already did a decent job in this post. Instead, I’m just going to review each app in turn and show how KeepScore improves upon them.

Score

Score is actually a decent app, and it’s where I got most of my inspiration for the design of KeepScore. The “new game” wizard in particular is a great idea – it’s simple, it’s intuitive, and it allows you to start up a game in seconds. However, Score suffers from a few flaws that make it nigh-unusable:

- The screen doesn’t stay awake. In a game like cribbage, where you need to update someone’s score every 20-60 seconds, this is unacceptable. When we played, the game kept grinding to a halt every time the phone fell asleep.

- The game doesn’t save automatically. My friends aren’t used to my Nexus One, so they kept accidentally hitting the home key or the back key. Each time, we would have to enter all our scores again.

- The buttons are too close together. When your users are going to be juggling a handful of cards or game pieces while simultaneously trying to guide a finger towards the smartphone screen, there’s no reason to bunch up the buttons so close together. In Score, it’s easy to accidentally decrement one player’s tally when you meant to increment another’s.

On top of this, Score just seems to suffer from sloppy execution. When you long-press on the “+” or “-” button, you get a popup allowing you to add a custom value, but it actually adds one less than whatever you enter. Many users have complained about this in the Android Market comments, but the dev doesn’t seem to have gotten the memo.

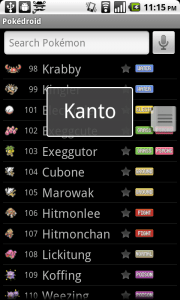

Scorer

Like Score, Scorer is a mix of good design and bad design. One feature I really like is the configurable buttons at the bottom – they make it easy to add large numbers to a player’s score (e.g. to add 12, press “+10” once and “+1” twice). Another highlight is the green and red increment markers next to each player’s name, which make it easy to see how much you’ve already added to someone’s score. (I borrowed both ideas for KeepScore.) Scorer also keeps the screen awake and saves automatically, although unfortunately it can’t save more than one game at a time.

Scorer’s biggest flaw, though, is just its basic layout design. Rather than having separate buttons for each user, Scorer requires you to tap a player’s name before altering their score. This doesn’t sound like a big deal, but in practice it makes scoring very cumbersome. When playing cribbage, my friends and I would often accidentally add a score to the wrong player, and then we would have to figure out how much we added, backtrack, and add it to the correct player.

Another problem is that the green/red markers only “commit” if you press the OK button. So if we wanted to make sure we could backtrack the correct amount, we’d have to keep pressing OK to add the score in. This meant at least three touches were required just to update a player’s score! Tap, tap, tap. It doesn’t sound like much, but it’s a minor inconvenience that adds up over the course of a game.

Advanced Tally Counter

I’m not even sure where to start with this one. This is a good example of the kind of graphic design I really hate: the developer has gone out of his way to deviate from the basic Android themes, and the result is an ugly and distracting presentation. On top of that, the app is very wordy and heavy on explanations. Touch the big button in the corner, and you’ll see a toast saying, “Please long click on this button to reset the counters.” Touch the back button and you’ll see “Press back again to exit the app.” Touch back twice and you’ll get a popup asking you to rate the app before you exit. Start up the app for the first time and you’ll get a popup asking you to download another app. And of course, there’s an ad banner over the top. The app seems determined to direct your attention toward everything except just keeping score.

Other than that, the app is pretty basic. Press “+” to increment by one, and press “-” to decrement. There’s no way to add larger values at once, and if you long-press on the “+” or “-” buttons, you’ll get a long list of hardware buttons you can use in place of the on-screen button. I find this feature pretty useless, though, given that more and more Android devices are getting rid of keyboards, buttons, and trackballs. Also, if you press the “+” or “-” button rapidly, the current score won’t update at first – it’ll just sort of vibrate for awhile until finally updating at the end. I found that confusing.

All in all, there’s no reason to use Advanced Tally Counter when there are less ugly and distracting alternatives. Also, the fact that the app has ad banners and a bewildering “Pro” version (I still can’t figure out what it does) reflects pretty poorly on the dev. Come on, dude. You’ve written a counting app. Are you really so hard-up that you need to try to make money off this thing?

Simple Score Sheet

First off, let me compliment the graphic design here. This is a case where a developer has deviated from the standard Android themes, but unlike Advanced Tally Counter, I think the result is really pleasing to the eye. The motif is simple and unobtrusive, and the custom font lends itself well to the whole “pen and paper” theme. Even the stylized buttons are cute and not at all distracting. So I give the developer high marks for designing a really beautiful app.

Unfortunately, the big problem with Simple Score Sheet is that it violates every principle of simple UI design. Whenever the developer had a choice between simplicity and complexity, he’s clearly chosen complexity. Just starting up a new game is like filling out a census form – it’s long, it’s tedious, and you have to think hard before you answer every question.

Just look at the screenshots above. Everything above “Start game” on the first screen is totally unnecessary for 99% of the app’s users. What’s the starting score? Who cares – I probably just want it to be zero! The whole “Game ends after…” and “Player with highest/lowest score wins” questionnaire is also the height of arrogance. Why do I need to tell the app who’s won the game? Why are you forcing me to start thinking about how many rounds the game has? Before I’ve started using your app, I don’t even know how it keeps track of rounds! I just want to start tallying some scores, damn it!

Even worse is the fact that the app will not let you complete the wizard unless you fill out all the information it deems necessary. If you try to press “Start game” without entering any information, it will complain: “Please enter a value for game ending option.” If you try to add a player without a name, it will complain again. All of these are pretentious moments where the developer is slapping the user on the wrist for not following his own complicated directions, like those old GPS navigation devices that would scold you for taking a detour. It makes the user think, and like the title of the famous book goes, Don’t Make Me Think!

Once you finally make it past the bureaucracy and into the scoring app itself, the usual complaints apply. It doesn’t automatically save, it’s hard to tell how much you’ve already added to someone’s score, and it’s hard to add values larger than 1. In fact, its system for adding large values is particularly bad. The way it works is that, if you long-press on the “+” button, the counter will start to increase on its own, accelerating as you keep holding it down. This would be pretty convenient, except that it also gets set off if you tap multiple times in quick succession. In practice, this means that the score will often start zooming off like a runaway car, and then good luck trying to get the value back to what it was before. It’s a neat idea, but it’s just not executed very well.

KeepScore

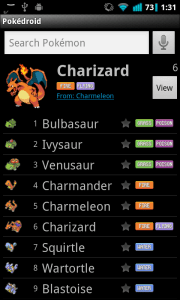

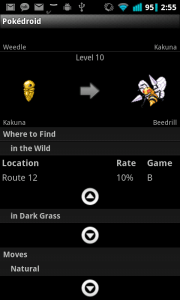

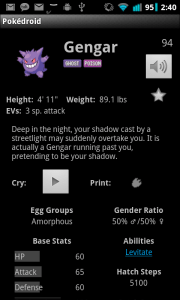

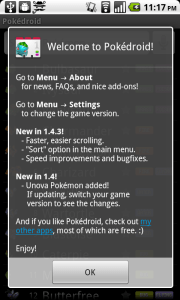

Enter KeepScore. KeepScore, I believe, is the best scoring app on the Android Market mostly because it just tries to do what the name says: keep score. The UI is designed to be as simple and unobtrusive as possible, without any distractions or extraneous options. Let’s walk through it step-by-step.

The startup screen and the “New Game” wizard are almost exactly the same as in Score. I added a “Resume Last Game” button, though, to provide a subtle hint that the game will be saved automatically. Other than that, it’s pretty basic, and when you open the app for the first time, it’s clear what you need to do: pound the “New Game” button.

As you go through the “New Game” wizard, all information except for the number of players is optional. If no players are named, then the name simply displays as “Player 1,” “Player 2,” etc. (Contrast this with Score, where only blank text is shown.) The scoring interface itself is very simple – two big buttons for each player, evenly spaced so that you’re not likely to accidentally press the wrong one.

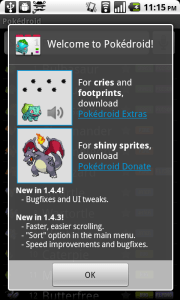

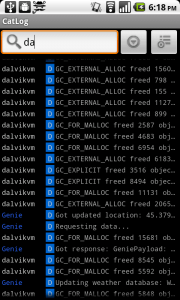

As soon as you start adding or subtracting values, you’ll see that the pane to the side starts to get filled with past values you’ve already entered. The most recent value stays bold for 10 seconds (configurable), during which time you can keep pressing “+” or “-” to change it. After 10 seconds of inactivity, the bolded value will unbold to indicate that it is no longer modifiable. At this point it’s now part of the scoring “history.”

All of this becomes clear to the user after just playing with the app for a few minutes, with no explanations needed. It’s a handy feature that eliminates a lot of the problems of “Oh, I accidentally added too much to your score. How much was it?” With KeepScore, you have a full history of every change you’ve made to a player’s score, so you don’t have to try to remember what you added. You can also long-press on the history to undo the last change. (Or you can just subtract, which is what I imagine most users will do.)

And of course, the app saves automatically. Whenever you exit, it displays a comforting toast saying “Game saved automatically,” just so the user can be sure that everything is good and saved. If you accidentally exit, you’ll notice upon reopening the app that the “Resume Last Game” button is no longer disabled. Most users will probably just make a beeline for that button, which is why I put it on the main screen.

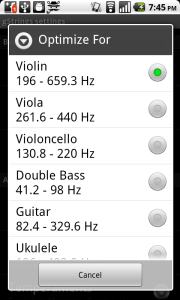

If you want to add values greater than 1, you can long-press on the “+” or “-” button. This pops up a dialog that allows you to input a number with the keyboard or just tap buttons with large increments like “+5” and “+10” (once again, configurable). It does worry me that this feature is “hidden” behind the long-press, but I think most users will figure it out if they know what they are looking for. Many of the other scoring apps let you long-press for additional options, so they might have set a precedent there. In any case, the app is still perfectly usable even without this feature.

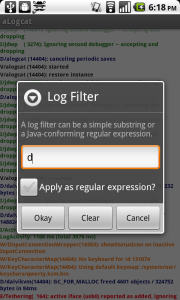

Unlike Simple Score Sheet, most of the configurations can be found in the Settings section rather than the main wizard, where it would just be clutter. There’s a concept in software engineering called “convention over configuration,” which basically means that the standard use-case should be the default, and the user should only need to use configurations if they want to do something unusual. I think KeepScore applies this principle pretty well, and that it makes for a smoother user experience. Any user actually looking for strange options (a starting score other than 0, customized button values, etc.) is probably savvy enough to know where to look for them.

Other neat options include the ability to save more than one game, a separate screen to explore the game’s complete scoring history, and the ability to change a player’s name mid-game. Most users will not bother with these options, though, so I tried to keep them out of the way as much as I could.

So there you have it. With just a little common sense and the restraint to not clutter up your app with unnecessary options and verbiage, you can create a dead-simple scoring app that actually beats pen and paper. It’s kind of sad that the Android Market went so long without an app that could do something so basic, but I’m just glad I finally have something worthy of my next cribbage game.

And the best part: KeepScore is free and open-source. You can download it from the Android Market here or get the source code here.