Update: Download the plugin on Github.

It’s a pretty common scenario when working with a Solr-powered search engine: you have a list of synonyms, and you want user queries to match documents with synonymous terms. Sounds easy, right? Why shouldn’t queries for “dog” also match documents containing “hound” and “pooch”? Or even “Rover” and “canis familiaris”?

A Rover by any other name would taste just as sweet.

As it turns out, though, Solr doesn’t make synonym expansion as easy as you might like. And there are lots of good ways to shoot yourself in the foot.

The SynonymFilterFactory

Solr provides a cool-sounding SynonymFilterFactory, which can be a fed a simple text file containing comma-separated synonyms. You can even choose whether to expand your synonyms reciprocally or to specify a particular directionality.

For instance, you can make “dog,” “hound,” and “pooch” all expand to “dog | hound | pooch,” or you can specify that “dog” maps to “hound” but not vice-versa, or you can make them all collapse to “dog.” This part of the synonym handling is very flexible and works quite well.

Where it gets complicated is when you have to decide where to fit the SynonymFilterFactory: into the query analyzer or the index analyzer?

Index-time vs. query-time

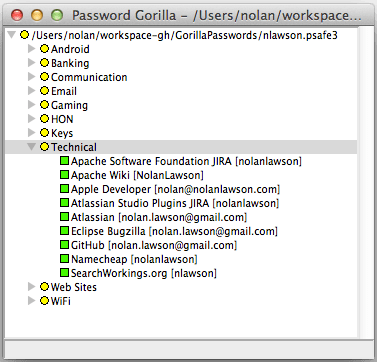

The graphic below summarizes the basic differences between index-time and query-time expansion. Our problem is specific to Solr, but the choice between these two approaches can apply to any information retrieval system.

Index-time vs. query-time expansion.

Your first, intuitive choice might be to put the SynonymFilterFactory in the query analyzer. In theory, this should have several advantages:

- Your index stays the same size.

- Your synonyms can be swapped out at any time, without having to update the index.

- Synonyms work instantly; there’s no need to re-index.

However, according to the Solr docs, this is a Very Bad Thing to Do(™), and apparently you should put the SynonymFilterFactory into the index analyzer instead, despite what your instincts would tell you. They explain that query-time synonym expansion has two negative side effects:

- Multi-word synonyms won’t work as phrase queries.

- The IDF of rare synonyms will be boosted, causing unintuitive results.

- Multi-word synonyms won’t be matched in queries.

This is kind of complicated, so it’s worth stepping through each of these problems in turn.

Multi-word synonyms won’t work as phrase queries

At Health On the Net, our search engine uses MeSH terms for query expansion. MeSH is a medical ontology that works pretty well to provide some sensible synonyms for the health domain. Consider, for example, the synonyms for “breast cancer”:

breast neoplasm

breast neoplasms

breast tumor

breast tumors

cancer of breast

cancer of the breast

So in a normal SynonymFilterFactory setup with expand=”true”, a query for “breast cancer” becomes:

+((breast breast breast breast breast cancer cancer) (cancer neoplasm neoplasms tumor tumors) breast breast)

…which matches documents containing “breast neoplasms,” “cancer of the breast,” etc.

However, this also means that, if you’re doing a phrase query (i.e. “breast cancer” with the quotes), your document must literally match something like “breast cancer breast breast” in order to work.

Huh? What’s going on here? Well, it turns out that the SynonymFilterFactory isn’t expanding your multi-word synonyms the way you might think. Intuitively, if we were to represent this as a finite-state automaton, you might think that Solr is building up something like this (ignoring plurals):

What you reasonably expect.

But really it’s building up this:

The spaghetti you actually get.

And your poor, unlikely document must match all four terms in sequence. Yikes.

Similarly, the mm parameter (minimum “should” match) in the DisMax and EDisMax query parsers will not work as expected. In the example above, setting mm=100% will require that all four terms be matched:

+((breast breast breast breast breast cancer cancer) (cancer neoplasm neoplasms tumor tumors) breast breast)~4

The IDF of rare synonyms will be boosted

Even if you don’t have multi-word synonyms, the Solr docs mention a second good reason to avoid query-time expansion: unintuitive IDF boosting. Consider our “dog,” “hound,” and “pooch” example. In this case, a query for any one of the three will be expanded into:

+(dog hound pooch)

Since “hound” and “pooch” are much less common words, though, this means that documents containing them will always be artificially high in the search results, regardless of the query. This could create havoc for your poor users, who may be wondering why weird documents about hounds and pooches are appearing so high in their search for “dog.”

Index-time expansion supposedly fixes this problem by giving the same IDF values for “dog,” “hound,” and “pooch,” regardless of what the document originally said.

Multi-word synonyms won’t be matched in queries

Finally, and most seriously, the SynonymFilterFactory will simply not match multi-word synonyms in user queries if you do any kind of tokenization. This is because the tokenizer breaks up the input before the SynonymFilterFactory can transform it.

For instance, the query “cancer of the breast” will be tokenized by the StandardTokenizationFactory into [“cancer”, “of”, “the”, “breast”], and only the individual terms will pass through the SynonymFilterFactory. So in this case no expansion will take place at all, assuming there are no synonyms for the individual terms “cancer” and “breast.”

Edit: I’ve been corrected on this. Apparently, the bug is in the Lucene query parser (LUCENE-2605) rather than the SynonymFilterFactory.

Other problems

I initially followed Solr’s suggestions, but I found that index-time synonym expansion created its own issues. Obviously there’s the problem of ballooning index sizes, but besides that, I also discovering an interesting bug in the highlighting system.

When I searched for “breast cancer,” I found that the highlighter would mysteriously highlight “breast cancer X Y,” where “X” and “Y” could be any two words that followed “breast cancer” in the document. For instance, it might highlight “breast cancer frauds are” or “breast cancer is to.”

Highlighting bug.

After reading through this Solr bug, I discovered it’s because of the same issue above concerning how Solr expands multi-word synonyms.

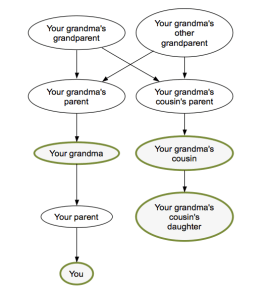

With query-time expansion, it’s weird enough that your query is logically transformed into the spaghettified graph above. But picture what happens with index-time expansion, if your document contains e.g. “breast cancer treatment options”:

Your mangled document.

This is literally what Lucene thinks your document looks like. Synonym expansion has bought you more than you bargained for, with some Dada-esque results! “Breast tumor the options” indeed.

Essentially, Lucene now believes that a query for “cancer of the breast” (4 tokens) is the same as “breast cancer treatment options” (4 tokens) in your original document. This is because the tokens are just stacked one on top of the other, losing any information about which term should be followed by which other term.

Query-time expansion does not trigger this bug, because Solr is only expanding the query, not the document. So Lucene still thinks “cancer of the breast” in the query only matches “breast cancer” in the document.

Update: there’s a name for this phenomenon! It’s called “sausagization.”

Back to the drawing board

All of this wackiness led me to the conclusion that Solr’s built-in mechanism for synonym expansion was seriously flawed. I had to figure out a better way to get Solr to do what I wanted.

In summary, index-time expansion and query-time expansion were both unfeasible using the standard SynonymFilterFactory, since they each had separate problems:

Index-time

- Index size balloons.

- Synonyms don’t work instantly; documents must be re-indexed.

- Synonyms cannot be instantly replaced.

- Multi-word synonyms cause arbitrary words to be highlighted.

Query-time

- Phrase queries do not work.

- IDF values for rare synonyms are artificially boosted.

- Multi-word synonyms won’t be matched in queries.

I began with the assumption that the ideal synonym-expansion system should be query-based, due to the inherent downsides of index-based expansion listed above. I also realized there’s a more fundamental problem with how Solr has implemented synonym expansion that should be addressed first.

Going back to the “dog”/”hound”/”pooch” example, there’s a big issue usability-wise with treating all three terms as equivalent. A “dog” is not exactly the same thing as a “pooch” or a “hound,” and certain queries might really be looking for that exact term (e.g. “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” “The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochy Show”). Treating all three as equivalent feels wrong.

Also, even with the recommended approach of index-time expansion, IDF weights are thrown out of whack. Every document that contains “dog” now also contains “pooch”, which means we have permanently lost information about the true IDF value for “pooch”.

In an ideal system, a search for “dog” should include documents containing “hound” and “pooch,” but it should still prefer documents containing the actual query term, which is “dog.” Similarly, searches for “hound” should prefer “hound,” and searches for “pooch” should prefer “pooch.” (I hope I’m not saying anything controversial here.) All three should match the same document set, but deliver the results in a different order.

Solution

My solution was to move the synonym expansion from the analyzer’s tokenizer chain to the query parser. So instead of expanding queries into the crazy intercrossing graphs shown above, I split it into two parts: the main query and the synonym query. Then I combine the two with separate, configurable weights, specify each one as “should occur,” and then wrap them both in a “must occur” boolean query.

So a search for “dog” is parsed as:

+((dog)^1.2 (hound pooch)^1.1)

The 1.2 and the 1.1 are the independent boosts, which can be configured as input parameters. The document must contain one of “dog”, “hound,” or “pooch”, but “dog” is preferred.

Handling synonyms in this way also has another interesting side effect: it eliminates the problem of phrase queries not working. In the case of “breast cancer” (with the quotes), the query is parsed as:

+(("breast cancer")^1.2 (("breast neoplasm") ("breast tumor") ("cancer ? breast") ("cancer ? ? breast"))^1.1)

(The question marks appear because of the stopwords “of” and “the.”)

This means that a query for “breast cancer” (with the quotes) will also match documents containing the exact sequence “breast neoplasm,” “breast tumor,” “cancer of the breast,” and “cancer of breast.”

I also went one step beyond the original SynonymFilterFactory and built up all possible synonym combinations for a given query. So, for instance, if the query is “dog bite” and the synonyms file contains:

dog,hound,pooch

bite,nibble

… then the query will be expanded into:

dog bite

hound bite

pooch bite

dog nibble

hound nibble

pooch nibble

Try it yourself!

The code I wrote is a simple extension of the ExtendedDisMaxQueryParserPlugin, called the SynonymExpandingExtendedDisMaxQueryParserPlugin (long enough name?). I’ve only tested it to work with Solr 3.5.0, but it ought to work with any version that has EDisMax.

Edit: the instructions below are deprecated. Please follow the “Getting Started” guide on the Github page instead.

Here’s how you can use the parser:

- Drop this jar into your Solr’s lib/ directory.

- Add this definition to your solrconfig.xml:

<queryParser name="synonym_edismax" class="solr.SynonymExpandingExtendedDismaxQParserPlugin">

<!-- TODO: figure out how we wouldn't have to define this twice -->

<str name="luceneMatchVersion">LUCENE_34</str>

<lst name="synonymAnalyzers">

<lst name="myCoolAnalyzer">

<lst name="tokenizer">

<str name="class">solr.StandardTokenizerFactory</str>

</lst>

<lst name="filter">

<str name="class">solr.ShingleFilterFactory</str>

<str name="outputUnigramsIfNoShingles">true</str>

<str name="outputUnigrams">true</str>

<str name="minShingleSize">2</str>

<str name="maxShingleSize">4</str>

</lst>

<lst name="filter">

<str name="class">solr.SynonymFilterFactory</str>

<str name="tokenizerFactory">solr.KeywordTokenizerFactory</str>

<str name="synonyms">my_synonyms_file.txt</str>

<str name="expand">true</str>

<str name="ignoreCase">true</str>

</lst>

</lst>

<!-- add more analyzers here, if you want -->

</lst>

</queryParser>

The analyzer you see defined above is the one used to split the query into all possible alternative synonyms. Synonyms that are exactly the same as the original query will be ignored, so feel free to use expand=true if you like.

This particular configuration (StandardTokenizerFactory + ShingleFilterFactory + SynonymFilterFactory) is just the one that I found worked the best for me. Feel free to try a different configuration, but something really fancy might break the code, so I don’t recommend going too far.

For instance, you can configure the ShingleFilterFactory to output shingles (i.e. word N-grams) of any size you want, but I chose shingles of size 1-4 because my synonyms typically aren’t longer than 4 words. If you don’t have any multi-word synonyms, you can get rid of the ShingleFilterFactory entirely.

(I know that this XML format is different from the typical one found in schema.xml, since it uses lst and str tags to configure the tokenizer and filters. Also, you must define the luceneMatchVersion a second time. I’ll try to find a way to fix these problems in a future release.)

- Add defType=synonym_edismax to your query URL parameters, or set it as the default in solrconfig.xml.

- Add the following query parameters. The first one is required:

| Param |

Type |

Default |

Summary |

| synonyms |

boolean |

false |

Enable or disable synonym expansion entirely. Enabled if true. |

| synonyms.analyzer |

String |

null |

Name of the analyzer defined in solrconfig.xml to use. (E.g. in the example above, it’s myCoolAnalyzer). This must be non-null, if you define more than one analyzer. |

| synonyms.originalBoost |

float |

1.0 |

Boost value applied to the original (non-synonym) part of the query. |

| synonyms.synonymBoost |

float |

1.0 |

Boost value applied to the synonym part of the query. |

| synonyms.disablePhraseQueries |

boolean |

false |

Enable or disable synonym expansion when the user input contains a phrase query (i.e. a quoted query). |

Future work

Note that the parser does not currently expand synonyms if the user input contains complex query operators (i.e. AND, OR, +, and –). This is a TODO for a future release.

I also plan on getting in contact with the Solr/Lucene folks to see if they would be interested in including my changes in an upcoming version of Solr. So hopefully patching won’t be necessary in the future.

In general, I think my approach to synonyms is more principled and less error-prone than the built-in solution. If nothing else, though, I hope I’ve demonstrated that making synonyms work in Solr isn’t as cut-and-dried as one might think.

As usual, you can fork this code on GitHub!