Note: I decided to put the summary and conclusion first, for the benefit of people stumbling across this article from a search engine. You guys might not want to read a wall of text. For everyone else who’s interested in the justification for these conclusions, keep reading.

Summary of boost methods

| Boost Method, with Example | Type | Input | Works With |

|---|---|---|---|

{!boost b}

|

Multiplicative | Function | lucenedismaxedismax |

| q={!boost b=myBoostFunction()}myQuery | |||

{!boost b} with variables

|

Multiplicative | Function | lucenedismaxedismax |

|

q={!boost b=$myboost v=$qq} &myboost=myBoostFunction() &qq=myQuery |

|||

bq (boost query)

|

Additive | Query | dismaxedismax |

|

q=myQuery &bq=_val_:”myBoostFunction()“ |

|||

bf (boost function)

|

Additive | Function | dismaxedismax |

|

q=myQuery &bf=myBoostFunction() |

|||

boost |

Multiplicative | Function | edismax |

|

q=myQuery &boost=myBoostFunction() |

Conclusions (TL;DR)

- Prefer multiplicative boosting to additive boosting.

- Be careful not to confuse queries with functions.

Recently I inherited a Solr project. Having never used Solr or Lucene before, but being well-versed in the dark arts of computational linguistics (from ye olde university days, anyway), I was eager to roll up my sleeves and get acquainted with it. I’d seen the formulas and proofs and squiggly stuff before – now I wanted to get my hands on something that really works.

And as I turns out, Lucene/Solr is a pretty slick piece of software. After over 10 years of development, it’s basically become a Swiss army knife for anything related to information retrieval. It’s got a bazillion different methods for parsing your queries, caching search results, tokenizing your stored text… It slices, it dices. But like any mature open-source project, it’s also got some inconsistencies and odd bits of historical baggage. Some of this is clear from the documentation, some of it isn’t.

One area that was especially unclear to me was “query boosting.” It’s a common scenario when building a search engine: you want to apply a boost function based on some static document attribute. For instance, maybe you want to give more preference to recent documents, or maybe you want to apply a PageRank score. The goal is to give your query results a gentle “nudge” in a certain direction, without completely throwing the TF-IDF score out with the bathwater.

As it turns out, there’s a good way of doing this in Solr. In fact, there’s more than one way. Let me explain.

In the Solr FAQs, the primary means for boosting queries is given as the following:

q={!boost b=myBoostFunction()}myQuery

It would be straightforward enough if this were the only method. But the DisMax query parser docs also mention bq, the “boost query” parameter, and bf, the “boost function” parameter. Furthermore, the ExtendedDisMax parser docs mention a third parameter, simply called boost, which they boast is “a multiplier rather than an addend, improving your boost results.” They also assert backwards compatibility with bq and bf.

At this point, my head was spinning. The Javadoc for Lucene’s Similarity.java describes just one simple boost function. The formulas in that document make for pretty thick reading, but if you have some experience in IR, it’s at least something you can wrap your head around. But now it looks like we’ve got 4 different boost functions. Which one should you pick?

Well, in the code base I inherited, we wanted to boost the logarithm of a static attribute called “relevancy score,” which was a precomputed, query-independent value attached to each document. To boost this value, the previous developer had decided to use the {!boost b} syntax. So for the query “foo,” our parameter q would be:

{!boost b=log(relevancy_score)}foo

This seemed to work reasonably well, but I wanted to experiment with the other methods. In particular, I wanted to see if I could abstract away the boost and keep it in a separate parameter, rather than doing ugly string manipulation of the q variable.

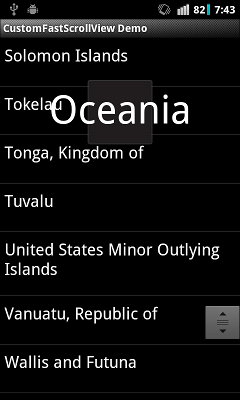

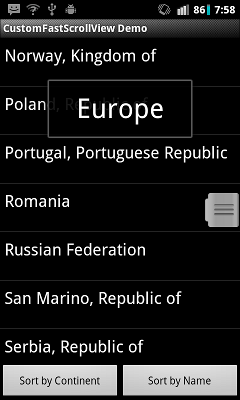

So I set up a simple test to compare all the different ways of applying boosts in Solr. These tests were run on Solr 3.5.0, using an index with about 4 million documents crawled from the web. I tested the three most popular query parsers – lucene, dismax, and edismax – and tried all four boost methods. For good measure, I also threw in a slightly different formulation of the {!boost b} method, which looks like this:

q={!boost b=$boostParam v=$qq}

&boostParam=...

&qq=...

… where boostParam and qq can be any string; they’re just variable references.

For each boost method, I queried 1000 documents and took the MD5 sum of each result set, in order to figure out which queries were identical. I tested several queries to ensure that my findings were consistent. The script I wrote is on GitHub if you want to check my work.

Below are my results for the query “diabetes” (my documents were healthcare-related), plus color-coding to show which result sets were identical. I also tried to give meaningful names to the result sets, based on what I could gleam from the Solr documentation.

| Boost Method | Lucene Parser |

DisMax Parser |

EDisMax Parser |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic (no boost) | No change | No change | No change |

| q=diabetes | |||

{!boost b} |

Multiplicative boost |

Multiplicative boost |

Multiplicative boost |

| q={!boost b=log(relevancy_score)}diabetes | |||

{!boost b} with variables |

Multiplicative boost |

Multiplicative boost |

Multiplicative boost |

| q={!boost b=$myboost v=$qq} &myboost=log(relevancy_score) &qq=diabetes |

|||

bq (boost query) |

No change | Additive boost | Some other additive boost? |

| q=diabetes &bq=log(relevancy_score) |

|||

bf (boost function) |

No change | Boost function, additive |

Boost function, additive |

| q=diabetes &bf=log(relevancy_score) |

|||

boost |

No change | No change | Multiplicative boost |

| q=diabetes &boost=log(relevancy_score) |

(Don’t worry about the “multiplicative” and “additive” stuff – we’ll get to that later.) Using debugQuery=on, we can see how Solr is parsing these queries. This helps make a lot more sense out of the results pattern:

| Boost Method | Parsed Query |

|---|---|

| Basic | text:diabetes |

{!boost b} or boost |

BoostedQuery(boost( text:diabetes, log(double(relevancy_score)))) |

bq with DisMax |

+DisjunctionMaxQuery( (text:diabetes)) () text:log text:relevancy_score |

bq with EDisMax |

+DisjunctionMaxQuery( (text:diabetes)) (text:log text:relevancy_score) |

bf with DisMax/EDisMax |

+DisjunctionMaxQuery( (text:diabetes)) FunctionQuery(log(double(relevancy_score))) |

A few insights leap out from looking at these tables. First off, it’s a relief to see that {!boost b} does indeed work the same with or without the variables. I think the variables are nice, because they abstract away the boost function from the query. The syntax is a little verbose, though.

Second, I was obviously barking up the wrong tree with bq (“boost query”), because it parses my function like a query. I.e., it’s literally looking for text containing “log” and “relevancy_score.” I realized later that this is because bq takes a query, not a function. Now, bq may be useful for cases where you’d want to boost a particular query – for instance, say you’ve got a sweetheart deal with Sony, so you want to add bq=manufacturer:sony^2. But it’s not useful for boosting static attributes.

Also, according to this thread on the Solr mailing list, bq and bf are essentially two sides of the same coin. Any query can be expressed as a function (using _val_:"..."), and any function can be expressed as a query (using query({!v=...})). So bq and bf are functionally equivalent, and historically one was just a shortcut to the other. Chris Hostetter, an original Solr contributor, fills us in on the story:

[T]he existence is entirely historic. I added bq because i needed it, and then i added bf because the _val_:”…” syntax was anoying [sic].

Third, it’s interesting to note that bq actually behaves differently with the DisMax parser vs. the EDisMax parser. The Lucid Imagination documentation suggests that they should be the same:

the additive boost functions of DisMax (bf and bq) are also supported

… but apparently, EDisMax behaves slightly differently from DisMax, because it automatically conjoins the “log” and “relevancy_score” tokens, which changes the results. That’s something worth considering if you’re already making use of bq.

So finally, that just leaves a proper analysis of the “multiplicative boost” (shown in green) and the “boost function, additive” (shown in blue). Both seem reasonable, so which one is the right solution?

From looking at the parsed queries, it seems that here we’ve finally found the multiplicative/additive split alluded to in the documentation. The bf (“boost function”) simply runs two separate queries – the main query and the boost query – and then takes the disjunction of the two using DisjunctionMaxQuery. That is, it just adds the scores together.

The {!boost b} and boost methods, on the other hand, apply a true multiplicative boost, using BoostedQuery. That is, they multiply the boost function’s score by whatever score would normally be spit out. This method is more faithful to the Lucene Javadoc for Similarity.java, and it seems to be the recommended choice, given how dismissively the word “additive” is tossed around in the documentation.

So basically, this is the boost you’re looking for. If you’re using the default lucene parser or the dismax parser, go with the {!boost b} method. If you’re using edismax, though, take advantage of the nice boost parameter and use that instead.

This is why I’ve rejected

This is why I’ve rejected