For the holidays, I gave myself a little experiment: build a small web app for my wife to manage her travel itineraries. I challenged myself to avoid editing the code myself and just do it “vibe” style, to see how far I could get.

In the end, the app was built with a $20 Claude “pro” plan and maybe ~5 hours of actual hands-on-keyboard work. Plus my wife is happy with the result, so I guess it was a success.

There are still a lot of flaws with this approach, though, so I thought I’d gather my experiences in this post.

The good

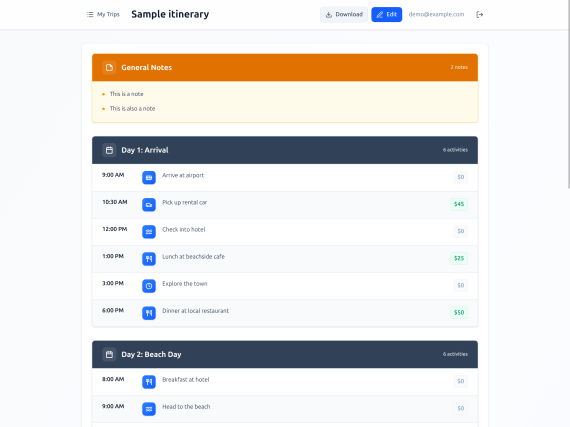

The app works. It looks okay on desktop and mobile, it works as a PWA, it saves her itineraries to a small PocketBase server running on Railway for $1 a month, and I can easily back up the database whenever I feel like it. User accounts can only be created by an admin user, which I manage with the PocketBase UI.

I first started with Bolt.new but quickly switched to Claude Code. I found that Bolt was fine for the first iteration but quickly fell off after that. Every time I asked it to fix something and it failed (slowly), I thought “Claude Code could do this better.” Luckily you can just export from Bolt whenever you feel like it, so that’s what we did.

Bolt set up a pretty basic SPA scaffolding with Vite and React, which was fine, although I didn’t like its choice of Supabase, so I had Claude replace it with PocketBase. Claude was very helpful here with the ideation – I asked for some options on a good self-hosted database and went with PocketBase because it’s open-source and has the admin/auth stuff built-in. Plus it runs on SQLite, so this gave me confidence that import/export would be easy.

Claude also helped a lot with the hosting – I was waffling between a few different choices and eventually landed on Railway per Claude’s suggestion (for better or worse, this seems like a prime opportunity for ads/sponsorships in the future). Claude also helped me decipher the Railway interface and get the app up-and-running, in a way that helped me avoid reading their documentation altogether – all I needed to do was post screenshots and ask Claude where to click.

The app also uses Tailwind, which seems to come with decent CSS styles that look like every other website on the internet. I didn’t need this to win any design awards, so that was fine.

Note I also ran Claude in a Podman container with --dangerously-skip-permissions (aka “yolo mode”) because I didn’t want to babysit it whenever it wanted permission to install or run something. Worst case scenario, an attacker has stolen the app code (meh), so hopefully I kept the lethal trifecta in check.

The bad

Vibe-coding tools are decidedly not ready for non-programmers yet. Initially I tried to just give Bolt to my wife and have her vibe her way through it, but she quickly got frustrated, despite having some experience with HTML, CSS, and WordPress. The LLM would make errors (as they do), but it would get caught in a loop, and nothing she tried could break it out of the cycle.

Since I have a lot of experience building web apps, I could look at the LLM’s mistakes and say, “Oh, this problem is in the backend.” Or “Oh, it should write a parser test for this.” Or, “Oh, it needs a screenshot so it can see why the CSS is wrong.” If you don’t have extensive debugging experience, then you might not be able to succinctly express the problem to an LLM like this. Being able to write detailed bug reports, or even have the right vocabulary to describe the problem, is an invaluable skill here.

After handing it over from Bolt to Claude Code and taking the reigns myself, though, I still ran into plenty of problems. First off, LLMs still suck at accessibility – lots of <div>s with onClick all over the place. My wife is a sighted mouse user so it didn’t really matter, but I still have some professional pride even around vibe-coded garbage, so I told Claude to correct it. (At which point it promptly added excessive aria-labels where they weren’t needed, so I told it to dial it back.) I’m not the first to note this, but this really doesn’t bode well for accessible vibe-coded apps.

Another issue was performance. Even on a decent laptop (my Framework 13 with AMD Ryzen 5), I noticed a lot of slow interactions (typing, clicking) due to React re-rendering. This required a lot of back-and-forth with the agent, copy-pasting from the Chrome DevTools Performance tab and React DevTools Profiler, to get it to understand the problem and fix it with memoization and nested components.

At some point I realized I should just enable the React Compiler, and this may have helped but didn’t fully solve the problem. I’m frankly surprised at how bad React is for this use case, since a lot of people seem convinced that the framework wars are over, since LLMs are so “good” at writing React. The next time I try this, I might use a framework like Svelte or Solid where fine-grained reactivity is built-in, and you don’t need a lot of manual optimizations for this kind of stuff.

Other than that, I didn’t run into any major problems that couldn’t be solved with the right prompting. For instance, to add PWA capabilities, it was enough to tell the LLM: “Make an icon that kind of looks like an airplane, generate the proper PNG sizes, here are the MDN docs on PWA manifests.” I did need to follow up by copy-pasting some error messages from the Chrome DevTools (which required even knowing to look in the Application tab), but that resolved itself quickly. I got it to generate a CSP in a similar way.

The only other annoying problem was the token limits – this is something I don’t have to deal with at work, and I was surprised how quickly I ran into limits using Claude as a side project. It made me tempted to avoid “plan mode” even when it would have been the better choice, and I often had to just set Claude aside and wait for my limit to “reset.”

The ugly

The ugliest part of all this is, of course, the cheapening of the profession as well as all the other ills of LLMs and GenAI that have been well-documented elsewhere. My contribution to this debate is just to document how I feel, which is that I’m somewhat horrified by how easily this tool can reproduce what took me 20-odd years to learn, but I’m also somewhat excited because it’s never been easier to just cobble together some quick POCs or lightweight hobby apps.

After a couple posts on this topic, I’ve decided that my role is not to try to resist the overwhelming onslaught of this technology, but instead to just witness and document how it’s shaking up my worldview and my corner of the industry. Of course some will label me a collaborator, but I think those voices are increasingly becoming marginalized by an industry that has just normalized the use of generative AI to write code.

When I watch some of my younger colleagues work, I am astounded by how “AI-native” their behavior is. It infuses parts of their work where I still keep a distance. (E.g. my IDE and terminal are sacred to me – I like Claude Code in its little box, not in a Warp terminal or as inline IDE completions.)

Conclusion

The most interesting part of this whole experiment, to me, is that throwing together this hobby app has removed the need for my wife to try some third-party service like TripIt or Wanderlog. She tried those apps, but immediately became frustrated with bugs, missing features, and ad bloat. Whereas the app I built works exactly to her specification – and if she doesn’t like something, I can plug her feedback into Claude Code and have it fixed.

My wife is a power user, and she’s spent a lot of time writing emails to the customer support departments of various apps, where she inevitably gets a “your feedback is very important to us” followed by zilch. She’s tried a lot of productivity/todo/planning apps, and she always finds some awful showstopper bugs (like memory leaks, errors copy/pasting, etc.), which I blame on our industry just not taking quality very seriously. Whereas if there’s a bug in this app, it’s a very small codebase, it’s got extensive unit/end-to-end tests, and so Claude doesn’t have many problems fixing tiny quality-of-life bugs.

I’m not saying this is the death-knell of small note-taking apps or whatever, but I definitely think that vibe-coded hobby apps have some advantages in this space. They don’t have to add 1,000 features to satisfy 1,000 different users (with all the bugs that inevitably come from the combinatorial explosion of features) – they just have to make one person happy. I still think that generative UI is kind of silly, because most users don’t want to wait seconds (or even minutes) for their UI to be built, but it does work well in this case (where your husband is a professional programmer with spare time during the holidays).

For my regular dayjob, I have no intention to do things fully “vibe-coded” (in the sense that I barely look at the code) – that’s just too risky and irresponsible in my opinion. When the code is complex, your teammates need to understand it, and you have paying customers, the bar is just a lot higher. But vibe coding is definitely useful for hobby or throwaway projects.

For better or worse, the value of code itself seems to be dropping precipitously, to be replaced by measures like how well an LLM can understand the codebase (CLAUDE.md, AGENTS.md) or how easily it can test its “fixes” (unit/integration tests). I have no idea what coding will look like next year, but I know how my wife will be planning our next vacation.